"Define, define, well-educated infant . . ."the (affected) character Don Adriano de Armado, Love's Labor Lost, 1.2.99

This is a quick note about definitions, invalid arguments, and misconceptions around AI. It's also partly an excuse for a brief homage to Sister Miriam Joseph.

Before beginning a legal analysis you must do the groundwork: determining the propositions/questions, determining the premises, and defining the terms in each.

Improper term definitions corrupt the entire analysis, begetting logical fallacies, equivocations of terms, and corrupted syllogisms. This can result in tortured readings of precedent and fallacious policy arguments.

In general, to be suitable in analysis, definitions should possess the following five qualities. Absent the first, however, ("Convertibility is the test of a definition"), there's considerable risk that your analysis will engage in equivocations. I quote the excellent Sister Miriam Joseph:

"A definition should be:

- Convertible with the subject, the species, the term to be defined. For example: A man is a rational animal. A rational animal is a man. The term to be defined and its definition coincide perfectly both in intension and in extension; hence they are always convertible. Convertibility is the test of a definition. A statement is convertible if it is equally true with the subject and the predicate interchanged.

- Positive rather than negative. A violation of this rule is: A good man is one who does not harm his fellow men. (It is not very enlightening merely to tell what something is not)

- Clear, symbolized by words that are neither obscure, vague, ambiguous, nor figurative. A violation of this rule is Samuel Johnson's famous definition of a network: "Network is anything reticulated or decussated, at equal distances, with interstices between the intersections."

- Free from a word derived from the same root as the word to be defined. A violation of the rule is a definition like the following: Success is succeeding in whatever you undertake.

- Symbolized by a parallel, not mixed, grammatical structure; for example;: a gerund should be used to define a gerund: an infinite, to define an infinitive. The following are violations: Pessimism is when a person looks on the dark side of everything. To cheat is defrauding or deceiving another."

(emphasis added) The Trivium - The Liberal Arts of Logic, Grammar, and Rhetoric.

I refer to these hereafter as the Rules.

Failure to honor the Rules is not dispositive of a corrupted definition and analysis, but should certainly sound alarm bells (again, especially if the convertibility isn't satisfied). In the context of AI, one must generally include some technical characteristics in the definition so as to satisfy convertibility.

Enthusiasm around AI has begotten many improper analyses based upon improper definitions. Here I focus upon Generative AI (“genAI”). Specifically, these definitions lack sufficient technical character so as to be convertible under the first Rule and will often fail many of the other Rules. When improperly defined in this manner, genAI systems stop being machines with concrete inputs and outputs and risk becoming, e.g., philosophical bogeyman that turn "Platonic ideas" into JPEGs.

While there are MANY examples of this in the past 2-3 years, I think the best way to appreciate this problem is to compare:

- Professor Lemley's 2023/2024 article "How Generative AI Turns Copyright Upside Down" (the "Article"; identified in GREY herein); and

- The Copyright Office's 2025 Report on Copyright and Artificial Intelligence Part 2: Copyrightability (the "Report"; identified in GREEN herein).

(Incidentally, my quotes are in ANTIQUEWHITE and quotes from anything other than the Article, the Report, or myself in BLUE.)

Professor Lemley is an excellent legal scholar and I hope he'll pardon my using his (now ~three-year old) article for this purpose - it's possible his position has greatly changed in the intervening period.

Both the Article and the Report address the question "Does existing legal doctrine suffice to address copyrightability in view of genAI?" but arrive at entirely opposite conclusions.

Specifically, in nuce, Professor Lemley asserts in his Article that:

“Generative artificial intelligence (“AI”) will require us to fundamentally change how we think about creativity” and will require that we adopt a “prompt-based copyright system” which "[o]ur current legal doctrine is not well designed to support" obligating us to therefore upend “our two most fundamental copyright doctrines, the idea-expression dichotomy that governs protectability and the substantial similarity test for copyright infringement.”(emphasis added) Article, Consolidated from Pages 22 and 26. (N.b., Article Page Number citations are as the PDF appears in the SSRN link, not to the PDF pages; i.e., the "first" page is page 21)

In contrast, the Report concludes as follows:

"Based on the fundamental principles of copyright, the current state of fast-evolving technology, and the information received in response to the NOI, the Copyright Office concludes that existing legal doctrines are adequate and appropriate to resolve questions of copyrightability. Copyright law has long adapted to new technology and can enable case-by case determinations as to whether AI-generated outputs reflect sufficient human contribution to warrant copyright protection."(emphasis added), Report, Page 41

While, assuredly, this disparity arises from quite a number of factors, as a matter of analysis, the origins of the Article and the Report's departure predictably lie in their definitions.

The Report provides a definition for the general term "AI system" and defines "Generative AI" in a footnote.

In the NOI, the Office defined an AI system as a “software product or service that substantially incorporates one or more AI models and is designed for use by an end-user.” As components to larger systems, AI models consist of computer code and numerical values (or “weights”) designed to accomplish certain tasks, like generating text or images."(emphasis added) Report, Page 5

“Generative AI” refers to “application[s] of AI used to generate outputs in the form of expressive material such as text, images, audio, or video.” Artificial Intelligence Study: Notice of Inquiry, 88 Fed. Reg. 59942, 59948–49 (Aug. 30, 2023) (“NOI”).(emphasis added) Report, Footnote 1, Page 1

These, in themselves, are rather broad and sweeping definitions. Fortunately, as indicated in the footnote, the Report points to additional technical character for its definitions in the corresponding Notice of Inquiry (NOI), which recites:

The "Report Definition""Generative AI technologies produce outputs based on “learning” statistical patterns in existing data, which may include copyrighted works. Kim Martineau, What is generative AI?, IBM Research Blog (Apr. 20, 2023), https://research.ibm.com/blog/what-is-generative-AI (“At a high level, generative models encode a simplified representation of their training data and draw from it to create a new work that’s similar, but not identical, to the original data.”). The Office has defined “generative AI” and other key terms in a glossary at the end of this Notice."(emphasis added) NOI, Footnote 1, Page 1

"Artificial Intelligence (AI): A general classification of automated systems designed to perform tasks typically associated with human intelligence or cognitive functions. Generally, AI technologies may use different techniques to accomplish such tasks. This Notice uses the term “AI” in a more limited sense to refer to technologies that employ machine learning, a technique further defined below.

AI Model: A combination of computer code and numerical values (or “weights,” which is defined below) that is designed to accomplish a specified task. For example, an AI model may be designed to predict the next word or word fragment in a body of text. Examples of AI models include GPT-4, Stable Diffusion, and LLaMA.

AI System: A software product or service that substantially incorporates one or more AI models and is designed for use by an end-user. An AI system may be created by a developer of an AI model, or it may incorporate one or more AI models developed by third parties.

Generative AI: An application of AI used to generate outputs in the form of expressive material such as text, images, audio, or video. Generative AI systems may take commands or instructions from a human user, which are sometimes called “prompts.” Examples of generative AI systems include Midjourney, OpenAI’s ChatGPT, and Google’s Bard.

Machine Learning: A technique for building AI systems that is characterized by the ability to automatically learn and improve on the basis of data or experience, without relying on explicitly programmed rules. Machine learning involves ingesting and analyzing materials such as quantitative data or text and obtain inferences about qualities of those materials and using those inferences to accomplish a specific task. These inferences are represented within an AI model’s weights."(emphasis added) NOI, Glossary, Pages 16 and 17

As indicated, taken together, I refer to this as the "Report Definition."

While the NOI's glossary and the informal reference thereto from the Report are a bit verbose and disjointed, and while I'm not sure I agree with the machine learning definition (is a Support Vector Machine "machine learning" by this definition? Perhaps if one construes the learned hyperplane as a weight . . .), taken all together, the Report Definition as derived from the NOI is "ok." The NOI glossary's definition for "Generative AI" standing alone would be too broad (how is this different from an AI-utilizing search engine?), but coupled with the technical character in the footnote, and cross-referencing it with the other definitions and examples, the result is something relatively useful. Consider:

- [OK] / [CAUTION] Rule #1: The glossary "Generative AI" definition is mostly convertible if one includes the parenthetical in the footnote in its interpretation. That said, the Report is rather sweeping and so this simple, broad definition was probably chosen more to facilitate comments and policy discussions than rigorous analysis.

- [OK] Rule #2: The definition is positive, stating positive attributes.

- [OK] / [CAUTION] Rule #3: The necessity to cross-reference between glossary terms and to roll in the technical character of the footnote isn't ideal. Similarly, "generate outputs" could be construed many different ways as could "expressive material." Combined with the examples, however, the meaning is relatively clear.

- [OK] Rule #4: Again, I don't like tracing through the glossary, but if one does so, one avoids the circularity warned of in Rule #4.

- [CAUTION] Rule #5: Tracing the glossary, one encounters interminglings of noun structure and verb processes, but this is generally the least concerning of the Rules.

Despite the breadth and verbosity, likely resulting from the Report's desire not to prematurely bind its assessment and to appeal to a wide audience, what I do like about the Report's definition is that it is still careful to include technical character. That is, the footnote and glossary terms, when taken together, make clear that we're describing a machine with concrete operational behavior.

Still, for the limited purposes of this note, and acknowledging that there are many types of genAI architectures (diffusion models, generative adversarial systems, etc.; indeed, more are in active development as of 01/2026), I would suggest keeping in mind a more specific, more laconic, definition better facilitating close analysis, e.g.:

This "Note Definition"'GenAI' is a computer system configured to generate a composition of training instance elements from a latent space position indexed by a (textual, visual, etc.) prompt.

For example, a diffusion model may determine a latent space of image representations using a fixed Markov Chain and Contrastive Language-Image Pretraining (CLIP) (see, e.g., https://arxiv.org/abs/2110.02711), and then expose an interface for a user to sample the resultant latent space with a text-based prompt so as to produce a new image compositing elements of the training instances. While many such systems, particularly those based on CLIP, will use text-based prompts, one could use, e.g., a line art image as a prompt.

Assessed under the Rules:

- [CAUTION] / [OK] Rule #1: The definition is convertible, though I admit there may be some exotic outlier systems I'm unaware of. In any event, conversion is much more readily assessable in this laconic definition than in the Report Definition.

- [OK] Rule #2: The definition is positive, stating positive attributes.

- [OK] Rule #3: The definition is clear, though, admittedly, familiarity with latent spaces and the meaning of indexing thereto in the context of genAI is assumed. If you're not familiar with these concepts, I have some reservations about this video, but it's still a good intro: VIDEO

- [OK] Rule #4: Unlike many definitions you'll encounter on the internet, I took care NOT to recite "AI" in the definition, thereby avoiding circularity.

- [OK] Rule #5: The "configured to generate" comes close to a mix of noun structure and verb, but again, this is probably the least concerning of the rules.

Like the Report Definition, the Note Definition recites substantial technical character suitable for analysis.

By way of contrast, consider the Article's definition appearing in its initial footnote:

The "Article Definition"In this Essay, I use the terms “generative AI” and “foundation models” interchangeably to refer to AI systems that train on large general data sets and are capable of producing creative output in multiple domains. Large language models (“LLMs”) like ChatGPT are a particular type of foundation model focused specifically on text.(emphasis added) Article, Page 21

This definition is an attempt at a logical definition, i.e., defining a species ("genAI") by stating a genus ("AI") and a differentia ("AI systems that train on large general data sets and are capable of producing creative output in multiple domains").

Unfortunately, the AI genus is left vague, and the definition is generally hard to reconcile with various of the Rules.

- [PROBLEMATIC] Rule #1: The definition is generally not convertible. Not all Gen AI systems produce "creative output." The definition may suffice for a subspecies of genAI, but as it stands, has mis-matched extensions (the essence of convertibility). Convertibility also fails with the phrase "multiple domains." Why must the creative output be in more than one domain? Some image generation systems only produce image domain outputs. Are they not genAIs? Perhaps this was a typographical error in the Article (it's a little unclear, e.g., if "multi-domain" and "multi-modal" aren't meant to refer to the same thing). But the most important problem here is the definition's lack of technical character and consequent lack of convertibility, discussed in greater detail below.

- [PROBLEMATIC] Rule #2: This may be an unfair characterization, but since it does significantly affect the Article's analysis, I'd characterize "creative output" as an implied negation. I.e., if a genAI's output is not creative, then by this definition it is not genAI (this will manifest in the Article's analysis as Begging the Question, discussed below);

- [VERY PROBLEMATIC] Rule #3:The definition’s terms are "obscure, vague, ambiguous." What is "general" data? What is "creative"? The definition is on its face contradictory, first saying that the "capable of producing creative output in multiple domains" but then saying ChatGPT is a "model focused specifically on text." Again, it's not always clear if the Article has multi-modal data or something else in mind.

- [CAUTION/PROBLEMATIC] Rule #4: If one replaces "AI systems" with just "systems", then one avoids the circularity contrary to Rule #4. However, being a logical definition, the issue is still present in the ambiguity of the AI genus. Without "AI systems" the definition could just as readily read upon a search engine (which trains "on large general data sets and [is] capable of producing creative output in multiple domains").

- [OK] Rule #5: While there's some minor mixing, again, this is probably the least significant of the Rules, and so I won't belabor the issue (Sister MJ is wise to identify this issue - notation CAN affect substance - but often, if one is charitable, one can look past any ostensible defect).

As discussed below, this vague definition begets at least the following errors and fallacies in the Article:

- Equivocation of terms;

- Reification of legal fictions; and

- Begging the question

Below, I briefly discuss these errors and invite the reader to consider when, in our own reasoning, we may be falling into similar pitfalls.

Each of the three errors / fallacies are clearly seen once one rephrases the argument of the Article into a syllogism:

- (Major Premise) The idea-expression dichotomy legal fiction that "ideas are not copyrightable, only expression is" reflects what "copyright traditionally exists to reward", i.e., "the hard work of creation" which begets the expression.

- (Minor Premise) I (Professor Lemley) define genAI as a thing that produces an expression ("creative output") of an idea (prompt).

- (Conclusion) genAI produces what "copyright traditionally exists to reward."

Regarding errors of equivocation: The Article is conflating the "creative output" in the minor premise with the "hard work"/"expression" of the idea expression dichotomy in the major premise as if they were coeval in extension.

They are not coeval in extension.

The former is a more intensioned term that can be assessed under the less intensioned term of the legal fiction, as is the case in most legal analyses (this is generally the case in the Report). That is, a computer output may potentially be an instance of an expression (the Report glosses this as well when it says "generate outputs in the form of expressive material", but proceeds to use the terms in the appropriate extensions), but it cannot be the expression, qua expression, of idea-expression dichotomy. Accordingly, one cannot complete the syllogism by equating expression in idea-expression dichotomy with a concrete computer system operation. If one instead replaces the minor premise with the "Note" or "Report" definition above, which have greater technical character, the extension disparity becomes much more readily manifest.

(Attempting to make terms coeval that are not coeval begets an awkward mischaracterization of law, a reification, in the major premise, as discussed in the next section below, but let's continue to focus on equivocation here)

Though not the focus of the syllogism, a similar, and important, equivocation occurs upon the term "idea." The Article is conflating the prompt - typically, a specific, concrete literary text, analogous to software, or a handwritten note of instructions - with the legal fiction of an "idea."

Thus, through casual equivocations throughout its sentences, the Article has a tendency to exchange (often implicitly) aspects of the following terms:

- the idea of idea-expression dichotomy;

- the expression of idea-expression dichotomy;

- the original, copyrightable character of a literary text prompt; and

- the original, copyrightable character of an image output.

For example, consider the following two sets of quotes.

"I have to come up with the basic idea and tell it what I want. But the AI does the bulk of the work that copyright traditionally exists to reward. Dall-E 3 will even turn my basic request into a better prompt in order to give you better images.

(emphasis added) Article, Page 27"There may be a middle ground that centers copyright around whether enough human creativity goes into structuring the prompt. . . . This “prompt-based” approach ignores the creativity contributed by the AI, but continues to reward creativity contributed by users, assuming the prompt or series of prompts is detailed enough to rise to the level of creative choice. . . coming up with the right prompt to generate what you want will sometimes be an art form in itself."

(emphasis added) Article, Page 25-26 and Page 32

In the first quote, the Article celebrates #4 (image output) in connection with an alleged #1 (idea), which is in fact a #3 (a literary prompt; indeed, arguing #1, while acknowledging #3 when it says the AI "will even turn my basic request into a better prompt").

Similarly, in the second collection of quotes, the Article conflates the analysis of #3 (literary prompt) with the analysis of #4 (image output; they're two distinct analyses under current law, being distinct mediums) so as to tacitly argue an (alleged) corresponding interplay between #1 (ideas) and #2 (expressions).

Regarding the first quote's error, the Report provides an excellent example demonstrating why one must not conflate #1 (ideas) and #3 (prompts) when performing an analysis of #4 (image output)."Professor Daniel Gervais made a similar point with the following analogy: “If I walk into a gallery or shop that specializes in African savanna paintings or pictures because I am looking for a specific idea (say, an elephant at sunset, with trees in the distance), I may find a painting or picture that fits my idea,” but “[t]hat in no way makes me an author."(emphasis added) Report, Page 18

Similarly, regarding the second quote's error, casually conflating analyses of #3 (prompt) and #4 (image) ignores the fixation requirement and its connection with medium and expression in copyright law.

For example, in his joint authorship analysis in Gaiman v. McFarlane, Judge Posner carefully teased apart and recognized the disparity of expressive mediums:

"We are mindful that the Ninth Circuit denied copyrightability to Dashiell Hammett's famously distinctive detective character Sam Spade . . . The Ninth Circuit has killed the decision . . . but even if the decision were correct and were binding authority in this circuit, it would not rule this case. The reason is the difference between literary and graphic expression. The description of a character in prose leaves much to the imagination, even when the description is detailed--as in Dashiel Hammett's description of Sam Spade's physical appearance in the first paragraph of The Maltese Falcon: "Samuel Spade's jaw was long and bony, his chin a jutting v under the more flexible v of his mouth. His nostrils curved back to make another, smaller, v. His yellow grey eyes were horizontal. The v motif was picked up again by thickish brows rising outward from twin creases above a hooked nose, and his pale brown hair grew down--from high flat temples--in a point on his forehead. He looked rather pleasantly like a blond satan." Even after all this, one hardly knows what Sam Spade looked like. But everyone knows what Humphrey Bogart looked like.(emphasis added) Gaiman v. McFarlane, 360 F.3d 644, 660-61 (7th Cir. 2004)

This second error of equivocation is also, as discussed in the next section, an error of reification.

Regarding errors of reification: As mentioned, the syllogism attempts to recast the idea-expression dichotomy in the language of the definition in the minor premise, begetting a mischaracterization of law, forcing, in Procrustean fashion, the law into the more concrete language of the definition (i.e., reification).

At the outset it is critical to appreciate that copyright does not reward hard work as asserted in the Article. It rewards original work.

This is appropriate even from a commonsense perspective. The visual artist Kim Jung Gi, in his prime, drew with ease and facility - to mitigate his claim to copyright on the basis that he didn't do "enough hard work" in creating a specific piece would be absurd. We don't award medals to dishwashers.

It is, I suspect, because its definition has biased its initial perspective that the Article is curiously silent regarding Feist and the "sweat of the brow" doctrine. The Report, in contrast, with its more technical definition, is prepared to more explicitly discuss both. In Feist, the Supreme Court, focusing on factual compilations, explicitly rejected the “sweat of the brow” doctrine:

"Making matters worse, these courts developed a new theory to justify the protection of factual compilations. Known alternatively as "sweat of the brow" or "industrious collection, " the underlying notion was that copyright was a reward for the hard work that went into compiling facts . . . Without a doubt, the "sweat of the brow" doctrine flouted basic copyright principles . . . "Sweat of the brow" decisions did not escape the attention of the Copyright Office. When Congress decided to overhaul the copyright statute and asked the Copyright Office to study existing problems . . . the Copyright Office promptly recommended that Congress clear up the confusion in the lower courts as to the basic standards of copyrightability. The Register of Copyrights explained in his first report to Congress that "originality" was a "basic requisite" of copyright under the 1909 Act, but that "the absence of any reference to [originality] in the statute seems to have led to misconceptions as to what is copyrightable matter" . . . The Register suggested making the originality requirement explicit. Ibid. Congress took the Register's advice."And indeed, 17 U.S. Code § 102 now reads:(emphasis added) Feist Publ'ns, Inc. v. Rural Tel. Serv. Co., 499 U.S. 340, 352, 111 S. Ct. 1282, 1291 (1991)

Copyright protection subsists, in accordance with this title, in original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression . . .The focus upon originality, rather than "hard work", is also more consonant with the Constitution’s directive to Congress:(emphasis added) 17 U.S. Code § 102

"[the United States Congress shall have power] To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries."(emphasis added) Article I, Section 8, Clause 8 of the U.S. Constitution

The Article's loose equating of "creative output" with "original output" begets the tortured statement of the major premise above focusing upon "hard work" rather than "original work." This is effectively an attempt to reify the idea-expression dichotomy from a legal fiction into prompts and outputs. The Report, with its more technical definition, is not so similarly bound and can simply work with the precedent.

This is a prudent juncture to note that if one wanted to rewrite the argument of the Article using proper definitions, there are tools available for doing so. But, like the Report, they must honor extension with the terminology of doctrine and precedent.

This is also a prudent point for a brief digression about a fundamental error manifesting here in the reification, which also occurs in other areas of legal analysis, such as 101 subject matter in patent law and fancifulness in trademark.

Ideas cannot exist separately from expressions. Period.

In the copyright caselaw (and, mutatis mutandis in patent, trademark, etc.), in discussing the legal-fiction of idea-expression dichotomy, courts will frequently act as if ideas existed in some ethereal Platonic realm distinct from physical reality. This is an analytic expedient, reflecting the fact that terms with very, very wide extension ("animal") are conveniently thought of as being of a distinct character from very intensioned instances (the physical reality of my parents' semi-feral cat Boo). However, in the previous sentence, the "animal" fiction is never manifested as a reality, because it isn't a reality. The reality is six letters ("a-n-i-m-a-l") on your screen / printout coupled with the interpretative character of your mind.

"The medium is the message."Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, 1964.

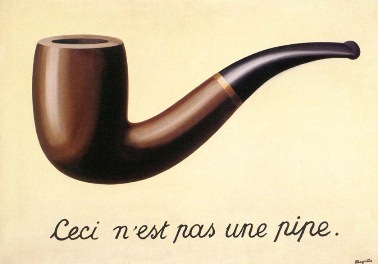

Rene Magritte, "The Treachery of Images", 1929 (the text reads: "This is not a pipe." N.b., it isn't.)

Rene Magritte, "The Treachery of Images", 1929 (the text reads: "This is not a pipe." N.b., it isn't.)

This reification error raises its head in patent law when flummoxed attorneys don't understand their Alice/101 subject matter rejections, misinterpreting an examiner or court's challenging of their chosen expression as being ignorance or malice rather than a legitimate analysis.

This reification error raises its head in trademark law when attorneys assume that "apples" have anything to do with "computers".

Etc., etc.

This error is also pervasive in discussions of AI and "general AI" whatever that is. Commentators casually equivocate terms without acknowledging when they slide between meanings (e.g., "What is my neural network thinking? How well does it need to reason before it's 'as good as' a human?"). Accordingly, before moving on, let me also briefly call the reader's attention to William James' comments on ignoring intensioned realities in favor of highly extensioned fictions:

"Let me give the name of "vicious abstractionism" to a way of using concepts which may be thus described: We conceive a concrete situation by singling out some salient or important feature in it, and classing it under that; then, instead of adding to its previous characters all the positive consequences which the new way of conceiving it may bring, we proceed to use our concept privatively; reducing the originally rich phenomenon to the naked suggestions of that name abstractly taken, treating it as a case of "nothing but" that concept, and acting as if all the other characters from out of which the concept is abstracted were expunged. Abstraction, functioning in this way, becomes a means of arrest far more than a means of advance in thought. ... The viciously privative employment of abstract characters and class names is, I am persuaded, one of the great original sins of the rationalistic mind"as well as James' second appearance in a similarly themed quote from the excellent Ernst Cassirer:(emphasis added) Wiliam James, THE MEANING OF TRUTH, Chapter 13, 1909

"For the reality of the phenomenon cannot be separated from its representative function; it ceases to be the same as soon as it signifies something different, as soon as it points to another total complex as its background. It is mere abstraction to attempt to detach the phenomenon from this involvement, to apprehend it as an independent something outside of and preceding any function of indication. For the naked core of mere sensation, which merely is (without representing anything), never exists in the actual consciousness; if it exists at all, it is the prime example of that illusion which William James called "the psychologist's fallacy." Once we have fundamentally freed ourselves from this illusion, once we have recognized that not sensations but intuitions, not elements but formed totalities, comprise the data of consciousness, we can only ask: what is the relationship between the form of these intuitions and the representative function they have to fulfill? Then it becomes evident that a genuine relation of reciprocity is present: the formation of intuition is the actual vehicle required by representation, and on the other hand the use of intuition as a means of representation unceasingly brings out new aspects and factors in intuition and forms it into an increasingly richer and more differentiated whole."(emphasis added) Ernst Cassirer, "The Philosophy of Symbolic Forms", 1957, the Ralph Manheim translation, Page 141

Reality is not a rebus puzzle whose solution lies within a mythical space beneath, and orthogonal to, the images and characters appearing upon its surface.

If you can keep the above in mind, Alice/101 rejections, trademark expression analysis, etc., become a great deal easier.

Moving on . . .

Regarding the Fallacy of Begging the Question: The Article, by its definition, assumes what it should be setting out to prove. Copyright protects original work. Rather than demonstrate how prompt-based sampling of latent spaces can beget original works, the Article simply assumes that doing so begets a "creative output" and then conflates this "creative output" in its analysis with the "original work" and "expression" of copyright as discussed above.

I won't spend too much time on this, but if one considers photobashing, which the existing copyright regime is well-suited to address, the Article does not explain why the technical character of genAI warrants different treatment, instead simply assuming that that's the case, and then extolling a handful of technical design choices as immutable laws of momentous philosophical import.

Such assumptions beget a number of questionable, or simply wrong, statements.

For example, the Article says:

"AI changes the economics of creativity, making a literally endless array of new content available for essentially no cost."Article, Page 22

This just isn't true, and its contrary is self-evident from the technical character of the Report and Note definitions. The "new" content is certainly not "endless" but limited by the size of the training instances and breadth of the resultant latent spaces. Neither is the "new content available for essentially no cost." Someone has to create the training instances, someone has to perform the resource intensive act of training the architecture, and even deployment/inference imposes energy costs. In total, this is likely thousands, if not millions (or more), of American dollars of cost.

Indeed, aside from financial costs, depending upon how one uses it, using an AI can be considerably MORE temporally expensive, imposing MORE upon the user's time than, say, photobashing. For example, consider:

- a visual artist who genuinely wishes to create something new for her audience; or

- an attorney who wishes to draft a tightly integrated legal document.

Most genAI systems do not share/expose their training data, and even if they did, it's exceptionally non-trivial (typically impossible) to infer exactly how the genAI composited elements from the training data into its latent space or into the output. There's active research in this area by applying autoencoders at intermediate layers to "infer" how the network is operating, but even if that operation were "understood", in accordance with the autoencoder, one would be describing a high-dimensional operation within the network using a crude low-dimensional proxy.

As mentioned, the Article's definition likewise biases its assessment of technical design choices, submitting copyright doctrine to (relatively) arbitrary design choices rather than (relatively) arbitrary design choices to copyright doctrine.

For example:

"And because copyright law requires only a bare minimum of originality, asking more than the simplest question may be enough to qualify for copyright protection . . . But if it does, the resulting copyright protection is going to be extremely narrow. It will not extend to the ideas for a painting or story, to underlying facts, or to functional elements of a prompt. And it won’t extend to the AI’s expression of those ideas or functional elements. Any resulting protection will have to triangulate somewhere between the two, finding creativity in some subset of prompt instructions that are sufficiently detailed to be neither ideas nor dictated by the ideas. And as generative AI increasingly rewrites the prompts for you, even many aspects of the prompts may not be copyrightable. The thing copyright will protect is not the core expression of the work, but a few peripheral elements on the border between idea and expression, whether in the text of the prompt itself or in extremely narrow strands of creativity in the AI-generated work that can somehow be traced to the creative elements of the underlying prompt. And protection for even those narrow elements may be in doubt, because most generative AI programs include a random seed to prevent the same prompt from generating the same output. That means that even careful prompting will not produce a deterministic outcome. Courts and the Copyright Office have rejected protection where the purported author set the conditions for a work to be created but could not control how it actually developed.(emphasis added) Article, Page 33

This is a tempest in a teapot, begotten by the Article's definition assuming inherent originality in genAI's technical character, rather than defining that technical character and then demonstrating how/if that character can beget original works. As it is, the Article doesn't address the following parallel:

- When photobashing, one may apply randomizing brushes and clone tools to beget similar, but different, results.

- In genAI, one may apply prompt constraints and perturb latent space indexings to beget similar, but different, results.

The Article does not explain why these are not merely differences of degree, rather than of kind, instead assuming a difference in kind by its definition. The Article accordingly assumes an unsubstantiated equivalence between the power of a tool and the quality of a tool. As evidenced by anyone who has tried to roast a chicken with a jet engine, this is not always the case.

The Report, in contrast, recognizes that nothing in the current technical topology necessarily warrants a change of analysis - one must simply distinguish the authors' non-original and original elements in the work. Consequently, less "powerful" tools (a digital photobashing brush) may often be more suitable for creating original content than "powerful" tools (an index into a high-dimensional latent space). The Report provides an example on Page 19 using a cat prompt and its image, which is essentially the same analysis described above in connection with Judge Posner in Gaiman v. Macfarlane, before saying:

[In connection with the generated cat picture and its prompt . . . ]Finally, as one final caution, appreciate that the Article's conflation of kind and degree begotten by its definition is likely what precipitated the Article's radical conclusions:

This prompt describes the subject matter of the desired output, the setting for the scene, the style of the image, and placement of the main subject. The resulting image reflects some of these instructions (e.g., a bespectacled cat smoking a pipe), but not others (e.g., a highly detailed wood environment). Where no instructions were provided, the AI system filled in the gaps. For instance, the prompt does not specify the cat’s breed or coloring, size, pose, any attributes of its facial features or expression, or what clothes, if any, it should wear beneath the robe. Nothing in the prompt indicates that the newspaper should be held by an incongruous human hand

. . .

Repeatedly revising prompts does not change this analysis or provide a sufficient basis for claiming copyright in the output. First, the time, expense, or effort involved in creating a work by revising prompts is irrelevant, as copyright protects original authorship, not hard work or “sweat of the brow.” Second, inputting a revised prompt does not appear to be materially different in operation from inputting a single prompt. By revising and submitting prompts multiple times, the user is “re-rolling” the dice, causing the system to generate more outputs from which to select, but not altering the degree of control over the process. No matter how many times a prompt is revised and resubmitted, the final output reflects the user’s acceptance of the AI system’s interpretation, rather than authorship of the expression it contains.”

(emphasis added) Article, Pages 19 and 20

"The result is that, increasingly, the things humans contribute in a collaboration with generative AI will be ideas and high-level concepts. AI will contribute the expression. That turns copyright law on its head."Article, Page 28

With a nod to the principle of maximum entropy, whenever your analysis begets a radical conclusion, it's often prudent to revisit your premises / definitions. It may be that everything is copacetic. But in accordance with entropy and the nature of our universe, it's probably best to see it as an invitation to run your definitions through the Rules again and be sure they're sufficiently bound to the domain of your analysis (here, technical character).

Though they may SEEM innocent, poor or loose definitions may blind one to proper legal arguments, counterarguments, and errors in one's reasoning. Especially in technically involved fields like AI, where facts are frequently misstated, one must be especially careful in one's groundwork to include appropriate technical character in accordance with the Rules.

Before closing, there's nothing wrong with "swinging for the fences" and in fairness to Professor Lemley, he often qualifies statements in his Article as being what "may" be the case in a future state. Many of my colleagues are uninterested in policy, legal philosophy, or wrestling with these concepts and I have infinitely more respect for practitioners who boldly risk error, than those tepid souls afraid to be anything other than "always right."

But regardless of where you end up, it's usually prudent to briefly genuflect to Sister MJ before you begin.